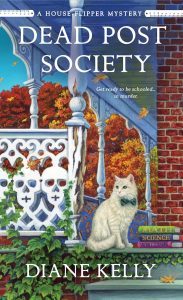

Dead Post Society

Read the Excerpt

Chapter One

Little creature, form’d of Joy and Mirth

– William Blake, “The Notebook of William Blake”

Whitney Whitaker Flynn

Tick.

Tock.

Tick.

Tock.

Has a clock ever moved so slow? I didn’t think so. It felt like time had slowed to a crawl in the hospital’s maternity ward waiting room.

The entire family was gathered there—other than Buck and Colette, of course. They were in the delivery room. But my Aunt Nancy and Uncle Roger grasped each other’s hands, anxiously awaiting the arrival of their newest grandbaby. Colette’s parents paced. My mother sat by my side, flipping through the most recent issue of Southern Living, though she was too full of nervous energy to pay the pages any real attention.

My father, who ran an otolaryngology practice nearby, had popped over to the hospital as often as he could, during his lunch break and whenever he had a gap in his appointment schedule. “Is the baby here yet?” he’d ask each time. “Not yet,” we’d say. He’d snap his fingers or swing an arm in an aw-shucks gesture. “Maybe she’ll have arrived by the time I get back.” Off he’d go again.

My husband Collin, a homicide detective for the Metro Nashville Police Department, had stayed with us at the hospital as long as he could, but he’d had to leave an hour ago to interview a witness. Important jobs like his didn’t come with predictable, convenient hours.

Dad had finished his shift and returned to the waiting room when—finally!—we heard an unmistakable sound. Footsteps coming up the hall. But not just any footsteps. Ones produced by large feet in cowboy boots.

We stood in unison when my cousin Buck strode up. Buck and I bore such a strong resemblance that people often mistook us for siblings rather than cousins. We were both tall with blonde hair and blue eyes. Buck was bulky, and sported a full beard. I could pull off a girly look when I needed to, but most days I left my face bare and pulled my hair back into a pony tail or messy bun to keep it out of the way. No sense getting myself all fixed up to do carpentry work when I’d be sweaty and covered in dust by the end of the day.

Buck’s wife Colette, who also happened to be my best friend, had been in labor for over sixteen hours with their first child. She’d been admitted to the hospital just before midnight the preceding day, and it was after four o’clock in the afternoon now. Buck’s thick blond hair was a wild mess, no doubt from him running anxious fingers through it. His beard, which he normally kept neatly trimmed, appeared bushier today, and there was stubble on his neck. His Western shirt was rumpled, and his face drooped with exhaustion. Nevertheless, his blue eyes sparkled with pure joy. “Y’all want to come meet Marigny?”

Did we ever! Of course, a limited number of visitors were allowed at one time, and grandparents were entitled to priority viewing. Though I knew my uncle Roger and aunt Nancy were dying to see their new grandchild, they deferred to Colette’s parents. Aunt Nancy extended her arm in invitation. “Colette did the heavy lifting. Why don’t you two go first?”

Colette’s mother was already on her way. “Thanks, Nancy!” she called back over her shoulder as her husband scrambled to keep up.

While Colette’s parents went to meet their new granddaughter, Buck stepped over to me, his parents, and my parents. Buck held up his phone so we could see his screen, and proceeded to scroll through photos and videos he’d taken of his brand-new baby. There were dozens. I couldn’t help but smile, both at the adorable, chubby baby with dark curls and the fact that Buck seemed to have memorialized every second of her existence so far. We women oohed, aahed, and dabbed at the happy tears in our eyes, while the men commented on Marigny’s extraordinary vigor as she belted out her best cry like a baby banshee.

“She’s certainly got some lungs on her!” Uncle Roger proclaimed with a grin.

Aunt Nancy put her hands on her hips and came to her granddaughter’s defense. “You’d be screaming, too, if everything you knew changed in an instant.”

True. Marigny had gone from a dark, warm, relatively quiet place to the bright lights and cool air of hospital room, full of unfamiliar sights and sounds. In the video clip, Colette cuddled the swaddled baby to her chest and spoke in soft, soothing tones, doing her best to assure her little girl that this new world she found herself in was a wondrous, loving place. She did a good job of it. In just a few seconds, the baby’s cries had settled into little more than adorable hiccups.

After Buck showed us all the pics and footage, he excused himself to go back to his wife’s bedside. Fifteen minutes later, Colette’s parents returned, and my aunt and uncle rushed down the hall to meet their granddaughter. I fidgeted in my seat, eager to meet the baby.

Finally, Uncle Roger and Aunt Nancy came back, and it was my turn. My parents trailed me as I hurried down to the room, a huge bouquet of assorted pink flowers in my hands. Dad opened the door for me. Colette lay in bed, her daughter held tight in the crook of one arm while she gently stroked her cheek with the back of her other hand. Buck was perched on the bed beside them, one arm around his wife’s shoulders, the other curved around the baby. A nurse in blue scrubs stood to the other side of the bed with her back to the door, making adjustments to the monitors and other myriad equipment that had been used during the birthing process.

“Congratulations!” I called in a stage whisper, wanting to show my excitement but not startle the baby.

Colette’s smile was broad and bright. “The flowers are beautiful, Whitney! Thank you.”

I set the vase on a side table, and got my first good gander at Marigny. She was named after a neighborhood in Colette’s childhood hometown of New Orleans. Buck and Colette had already decided they’d call her Mari for short. With Mari wrapped tightly in a lightweight blanket and a knit beanie on her head, only her face was visible. She was such a pretty little thing! “She looks like you, Colette.”

“Thank goodness!” Buck said, causing the rest of us to chuckle.

“Hey, little Mari.” I reached out and ran a hand lightly down her blanket-covered arm. “I’m so glad to meet you.”

She replied with a mew-like sound very similar to the noises my cat Sawdust had made when he was a kitten.

Colette beamed down at her daughter. “Isn’t she the most precious thing you’ve ever seen?”

“For sure,” I agreed. “She’s perfect.”

My mother concurred. “Absolutely adorable.”

Being a medical doctor, my dad was more concerned with her health than her cuteness. “Her color looks good. How’s her muscle tone?”

“She can bench press two-twenty,” Buck teased.

Colette loosened the blanket and waved my father closer. “See for yourself.”

Her arms free now, Mari threw slow baby punches against an invisible foe. My father reached down and Mari grabbed his index finger with her left hand, wrapping all five of her teeny-tiny digits around it. “Wow!” he said. “That’s quite a grip.”

“The better to hold a hammer with,” Buck said.

Colette, who was a professional chef, wagged a finger. “Nuh-uh-uh. A mixing spoon.”

Time would tell which parent the beautiful baby would take after, or maybe she’d go her own way and blaze her own trail. It would be fun to find out.

Mari blinked several times in succession and made another mewling sound before her little eyes blinked several times and drifted closed in peaceful security.

“You’re a natural, Colette.” I cast a glance at Buck. “How does it feel to be a daddy?”

“Terrifying,” he admitted with a grin. “But terrific, too.”

My father gave Buck a pat on the back. “That’s exactly what fatherhood is. Terrifying but terrific.”

My mother glanced my way. Though she said nothing, her thoughts were written on her face. I want a grandbaby, too! As an only child, I bore full responsibility for assuring the family line continued. No pressure, right?

We admired the baby some more, her pert little nose, her rounded cheeks, the tiny bow of her lips. When a doctor and a second nurse entered the room a few minutes later, my parents and I took that as our cue to leave. We bade Colette and Buck goodbye with a round of hugs.

I stopped in the doorway and glanced back at the new bundle of joy. Mari was going to be so spoiled and loved. What a lucky little girl.

Chapter Two

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

– William Wordsworth, “I Wandered Lonely As a Cloud”

Whitney

Buck and I had never formally discussed taking a break from our house-flipping business, but our personal circumstances had led to a months-long hiatus. While I was busy adjusting to life as a new wife, Buck was busy being daddy to his beautiful baby girl. Mari had loose dark curls like her mother, and an enormous appetite and stubborn streak like her father. With her cute coos and adorable antics, she kept the entire family entertained, most of all her three female cousins who were only slightly older and considered the infant to be their dress-up doll. Mari also had me thinking that maybe, just maybe, I might be ready to move beyond being a cat mom to being mother to a little human being. But Collin and I had yet to celebrate our one-year anniversary. Any discussion of having a child should probably wait until we’d passed that milestone.

In the meantime, Buck and I had been working for Buck’s father, my uncle Roger. Uncle Roger ran Whitaker Woodworking, a carpentry business. Though I’d taken Collin’s last name and was now legally known as Whitney Flynn, I’d forever be a Whitaker, too.

My uncle had a new carpentry project in the works, his biggest yet, and he’d asked Buck and me to be involved. That’s how Buck and I found ourselves driving down a two-lane highway in Ridgetop, Tennessee, on a partly cloudy Monday morning in late July, the windows rolled down on my SUV to let in the fresh air. The windows also let in the chugga-chugga-chugga sound of a nearby freight train moving along the tracks, and the blast of its horn as it warned the world it was rolling into town.

As we approached our destination, we came upon a long, six-foot high wall of red brick surrounding the expansive property. A few sections of the wall had crumbled, while others still stood straight a century after they’d been erected, a testament to the skill of the masons who’d built them.

I braked and turned into the entrance of the boarding school. Uncle Roger had told us that the institution closed in the early 1980’s and the property had since languished on the market, few people having use for a large facility of the type in what used to be the middle of nowhere. The school sat twenty miles north of Nashville and twenty miles south of the Kentucky border. Though the eighteen acres on which it was situated might have been useful for agriculture, there were plenty of other parcels available nearby that would not have required buildings to be razed before crops could be planted. In recent years, however, urban sprawl had brought people closer to Ridgetop, and the site was now an easy eight-minute drive from the growing suburb of Goodlettsville.

An iron gate adorned with the school crest stood open at the entrance. The shield-like shape of the crest reminded me of the shiny Metro Nashville Police Department badge Collin carried. The name of the school—Ridgetop Preparatory Academy—was written in a vintage font in the center of the crest, one word on each line. The border of the shield was wide with bisecting lines at short intervals, reminiscent of the railroad tracks we’d driven past on our way here.

I drove through the entry and continued on for a quarter mile past scattered trees and overgrown grass to the main parking lot. After pulling into a spot, I cut the engine and checked the clock on the dash. “We’re half an hour early.”

“That gives me time to take a nap before the others get here.” Buck put a finger to his lips in a shushing gesture, leaned his seat back, and closed his eyes.

Mari had been teething, keeping Buck and Colette up all night long. While I couldn’t blame my cousin for wanting to get some shuteye, he was going to be sorry company until the others arrived. It took less than ten seconds for him to start snoring. I pulled out my phone and kept myself busy for a few minutes playing Wordle. Once I’d guessed the word—DIARY—I slipped my phone back into my pocket and issued a soft sigh. Should’ve brought a book with me.

I glanced around. Ahead were three large brick buildings set in a U shape. The two buildings on either side were long, two-story structures with rows of rectangular windows that looked out onto what had once been a lawn. They’d been dormitories, most likely. The center building was wider and stood three stories high. The broad steps and empty flagpole in front told me it had served as the academic building.

While the history and craftsmanship of old buildings always interested me, what especially caught my attention was a structure barely visible through a stand of trees a hundred yards to the right. The size and shape told me it was a house. A Victorian, maybe? The rounded shape on the right looked like a turret room, a common feature in Victorian homes. It was difficult to tell for sure because ivy covered most of the structure, as if the earth had reached up to claim the house and was trying to drag it down into its clutches.

Curiosity and a desire to stretch my legs got the best of me. As quietly as I could, I retrieved my tool belt and my yellow hardhat with the daisy decals from the back seat, opened my door, and slid out of the SUV, gently pushing the door shut behind me. Buck’s loud snore continued through the open window. Good. I hadn’t disturbed him.

After donning my tool belt and hardhat, I approached the trees, kicking and stomping my way through the overgrown underbrush, thankful for the steel-toed work boots and coveralls that kept most of my skin inaccessible to mosquitos and ticks. No telling how many of the nasty little bloodsuckers might be out here, just waiting to sink their teeth into me.

I reached a shorter iron fence that had once delineated a yard. Dried, bent stalks of daffodils littered the lawn here and there, the yellow spring blooms long since withered, the bulbs scattered by scavenging squirrels. I slipped through the gate and looked up at the structure. Yep, definitely a Victorian. A brick one, though many of the bricks had come loose and fallen out, lying broken in the dirt as they slowly disintegrated into dust. Built before modern heating and air-conditioning systems, the house had numerous chimneys and large windows so that it could be warmed by fires in the winter and cooled by the outside breezes in the summer.

One of the porch posts had given way, the roof sagging to the left of the front door. Some the floorboards on the porch were gone entirely, and what remained were half rotten. My heart sank. The house appeared beyond repair. If only someone had saved it sooner.

I pushed aside the ivy that covered a window to the right of the porch, and pulled a rag from my tool belt to wipe the glass clean. The tiny bubbles in the panes and the irregular refraction of the sunlight told me the windows were originals, built of thick, wavy cylinder glass. I cupped my hands around my eyes and attempted to peer through the glass, but the curtains had been pulled closed inside, blocking any view into the interior.

I had never been able to resist the lure of an old house, no matter how dilapidated. I gingerly took the steps up to the porch. The roof immediately over the front door was still intact, though I found myself wishing for four-by-fours to shore it up. The structure could be unstable. As I proceeded to try the door despite my misgivings, I realized the same adjective could be applied to me—unstable. Anyone in their right mind wouldn’t risk entering this place.

The brass door knob came off in my hand. The other half fell to the floor inside with a klunk, leaving a gaping hole in the door. Oops. I felt bad for causing further damage to the place, but what did it matter? I reached through the hole and felt around for the deadbolt. Though my fingers found it, it was the type that required a key to turn. Such locks had been common once upon a time, but they were rarely installed now. They posed a safety hazard. If the key wasn’t left in the lock, a person could find themselves trapped in the house, unable to open the door to escape should a fire break out.

I pulled a small Phillips-head screwdriver from my belt and stuck it through the hole. It took more feeling around to find the screws holding the deadbolt in place against the door, but I managed to unscrew them, manually slide the bolt inward, and remove the apparatus. I supposed this technically counted as breaking and entering, but I’d replace the deadbolt after I took a look inside the house, so trespassing was my biggest crime here.

I opened the door and peered into a once-luxurious entry hall filled with period antiques. Wow! I felt like I’d magically time traveled to an earlier century. Despite the fact that the furniture was covered in dust, the pieces were intriguing, intricate and beautiful.

Footsteps in the dust on the floor told me that people had been in the house recently, probably to assess its condition. Leaving the door open behind me to allow the sunlight to shine in, I took a few tentative steps inside and glanced around. The poor condition of the exterior had given me low expectations for the interior. I was pleasantly surprised to see I’d been misled. The flooring wasn’t warped and, though the delightfully gaudy floral wallpaper was peeling in places, there were no water stains on the walls or ceilings, nor any tell-tale smell of mold.

To the left of the door was an antique hall tree with a mirror. Dark spots around the edge of the glass showed where moisture had seeped in, separating the silver from the backing, a common but charming flaw in antique mirrors. French doors lined with lace curtains stood ajar to the left. I walked over and peeked through the opening to see a traditional study, what passed for a home office in the era before everyone owned a personal computer. A brick fireplace was centered along the side wall. The upper part of the walls was painted a traditional green, while the lower sections sported knotty pine paneling. Knotty pine was one of my favorite woods because it proudly showed off its natural imperfections, swirls and irregular stripes and knotholes that resembled eyes.

I knew more about wood than anyone else might ever want to know. My uncle Roger had taught my cousins and me the ins and outs of carpentry when we were young, to my delight and my mother’s dismay. My mom had hoped her daughter would pursue a more dignified white-collar career but, from the time I’d fashioned my first birdhouse, I knew I was born to be a carpenter. I loved the feel of the different woods, their unique scents and characteristics. Like people, each type of wood had a distinct personality. Some were hard, others soft. Wood varied in its degree of elasticity and permeability, with some being easy to penetrate while others were much more difficult. Wood ranged from fine-grained to coarse, with fibers that varied from straight grains to spiral grains to interlocking grains. Good wood even made a distinctive sound. Quality timber, when struck, produced a ringing noise.

My focus shifted from the perimeter of the room to the interior. A large walnut desk sat in the center. An electric typewriter sat on a small table to the side. Tall, wide bookshelves stood in front of every window, blocking the glass. Why anyone would obscure the view of the trees outside when there was ample empty wall space for the shelves was beyond me. Then again, maybe the view was a distraction to the person who’d worked in this space. But who had that person been? And what had they worked on in here?

I pulled the doors open and tiptoed into the study. Why I felt the need to sneak, I don’t know. It wasn’t like anyone lived here anymore. The fact that the dust had not been disturbed in this room told me that nobody had been in here in years. Why hasn’t someone at least removed the antiques? Surely, they were valuable.

As I proceeded toward the desk, my eyes spotted two large, dark, misshapen stains on the hardwood floor. A liquid of some sort must have spilled on the flooring and remained for a prolonged period of time, allowing it to seep into the wood and cause permanent damage. Coffee perhaps. Or maybe red wine.

The spots reminded me of the stains on the floor at the Carnton plantation, a civil war site in the town of Franklin, just south of Nashville. I’d gone to the place on a school field trip in junior high. A critical battle had been fought in Franklin. Though the scale was close to that of the battle in Gettysburg, the battle of Franklin was much less known. During the conflict, Carnton had been used as a makeshift field hospital. Its floors had absorbed untold amounts of blood as amputations were performed on wounded Confederate soldiers, their severed limbs purportedly tossed out of the second-floor window into wagons waiting below. Creepy. Some said the place was haunted by the ghosts of soldiers who had died there. Of course, people had suffered in slavery at the site for decades before the war. While the house itself was beautiful, the history of the place was ugly and horrific.

Atop the desk were a faux-leather blotter, a landline phone with a curlicue cord, a stapler, and a heavy, old-fashioned tape dispenser. Next to the tape dispenser sat two smoothly polished apples fashioned from cherrywood and engraved in block letters. One read: Ridgetop Preparatory Academy Teacher of the Month April 1982. The other read: Ridgetop Preparatory Academy Teacher of the Month May 1982. The edge of the desk bore an unsightly light-colored scratch about three inches long. Sawdust had left a similar scratch on my tall dresser at home when he’d clung to the edge after unsuccessfully attempting to jump onto it from the bed. Even though the little runt had sorely miscalculated his trajectory, you had to admire his pluck. The desktop had other scratches, too, though they’d been disguised with strategic dabs of stain. The fact that the scratch on the edge had not been similarly addressed told me it must have been incurred shortly before the house had been put out of commission.

I pulled a drawer open to find it outfitted with a metal frame to hold hanging folders. Index tabs identified the contents of each folder. Drafts. Research/Notes. Reviews. Contracts/Royalty Statements.

Creak. I looked up at the ceiling. The noise had come from overhead, as if someone had taken a step in the room above. My heart pounded in my chest for a few beats, but when no other sound followed, I chuckled to myself. Surely, the creak had been nothing more than the sound of an old house settling.

I walked over to the table that held the electric typewriter. My grandparents had owned one like it, and I recalled pecking out letters on it when I was a young girl. On the right side of the typewriter was a stack of handwritten pages featuring perfect cursive penmanship. The pages were numbered at the top, and neatly ripped from legal pads. An empty coffee mug sat atop the pages, serving as a paperweight. To the left of the typewriter was a stack of typed pages lying face down, similarly held in place by a mug.

I fished the top page from each stack and compared the words on the typewritten page to those on the handwritten page. Yep. Whoever had worked at this typewriter had been transcribing the handwritten pages. The pages appeared to be a work of fiction. From the short excerpt alone, I couldn’t tell exactly what the story was about, but the mention of the Soviet Union told me it was set against the backdrop of the Cold War. The Soviet Union, like Ridgetop Preparatory Academy, had ceased to exist before I was born, though I knew the threat of a clash with the country had loomed over the lives of my parents and other Americans for decades.

As I turned to leave the room, I noted a variety of books on the shelves that had been placed before the front-facing windows. Curious, I stepped over to see what literary delights I might find. Eleven copies of a book entitled A Dark Day for Justice took up the top shelf, though they were different editions, some in hardcover and others in paperback. All bore the same image on the cover, a black background with a judge’s gavel in the center illuminated by a beam of light coming through a window covered in metal bars. The title was printed in dark red ink. The paperback cover also included a gold banner across the bottom that read #1 New York Times Bestseller. Impressive.

The author was someone named Dr. Irving Finster. I’d never heard of him. I opened one of the books and checked the yellowed copyright page. 1975. Turning the book over, I read the blurb on the back:

Bombs. Ballistic Missiles. Betrayal. In a world overshadowed by

the Cold War, a CIA operative finds himself burdened with secrets

that threaten to destroy his soul. In violation of department policy,

he confides in the one person he thinks he can trust without

question—his wife. But when Russia somehow learns the secrets

he’s shared, he’ll have to answer to the country he’s served. Will

the truth come to light, or will it be a dark day for justice?

The book sounded similar to the Tom Clancy novels my father had enjoyed years ago. I read on to find endorsements from other authors:

A daring and deftly executed debut novel. Dr. Irving Finster confronts the dangers and difficulties of being simultaneously an unsung hero and a severely conflicted human.

An epic for our times. Finster explores what happens when a man’s duty to his country clashes with his personal sense of morality.

I didn’t typically read thrillers because the graphic violence disturbed me, but this book sounded interesting and not excessively brutal, the conflicts more psychological than physical.

On the next shelf down was a single hardcover copy of a book by the same author. The title of this book was simply The Solution. Per the back cover copy, this book centered around a first-term mayor in a small, troubled town facing financial and social strife, a high crime rate, and competing, increasingly contentious factions. An enormous unabridged dictionary, a thesaurus, and classics filled the remaining shelves.

I walked across the front hall and into the parlor. A grand piano stood to the right of the fireplace, while a tufted velvet loveseat gave the parlor an additional air of elegance. A heavy piece of furniture had been placed in front of every window in this room, too. Men’s chairs with high backs had been placed in front of the windows on the side wall. I knew they were men’s chairs because they had arms. To accommodate the full skirts in fashion at the time, women’s chairs in the Victorian era lacked arms. Had whoever lived here blocked the windows to keep someone out? I could think of no other explanation for the odd placement of the furniture. “There’s definitely a story here.”